MicrofinanceFocus, 28 March 2012

Last month, the headlines of the world’s papers read déjà vu. “Suicides in India linked to microfinance debt.” “SKS Microfinance implicated in farmer suicides.” The headlines may have differed, but the article was one and the same, penned by Erika Kinetz of the Associated Press. SKS was appalled, calling the report “libelous” and “scurrilous.”

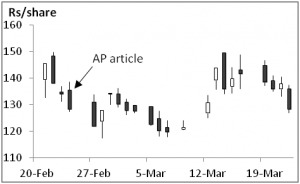

For what it’s worth, the damage has been minimal. SKS stock slid 4.25% on the day of the article, but recovered within a few days of trading. The slide shows little distinction from its already volatile trading pattern (Figure 1). Of course bad news can also cause lenders and investors to take a second look, or simply slow things down. One MFI manager told me of exactly this very reaction on the part of an Indian bank in the immediate days after the AP article. But the story got relatively little press in India, and no follow-up of significance. By now it’s reasonable to say that the microfinance sector in India can breathe a sigh of relief. Seeing bad news get swept back under the carpet can be quite satisfying, even if the stink remains.

This was, after all, just a minor aftershock. Just 18 months ago, the Indian microfinance industry went through one of the fastest reversals of any market. Within the space of a few months in late summer and early fall 2010, the dominant public narrative of Indian microfinance shifted from a rapidly growing sector catering driven by strong social goals to one where greed and utter disregard for common decency are the rule. Instead of being regarded as beneficiaries, microfinance customers started being cast as victims. This new narrative may no longer generate headlines, but it has yet to be replaced or successfully challenged. The reputation of Indian microfinance has not been restored.

Walking down memory alley

What did happen to the sector’s reputation in India? Largely, it was the juxtaposition of two narratives: an alleged avalanche of client suicides in Andhra Pradesh and the millions being reaped by the owners of SKS in its public offering. I have written before that this juxtaposition was no random alignment of events, but rather a well-engineered political maneuver on the part of the sector’s long-time opponents. Nothing I have learned since has made me change my mind on this point. However, recent revelations about what the industry leaders knew during and after those momentous months have deeply disappointed and made me increasingly doubtful of their ability to repair the sector’s tarnished image.

The industry did get some things right. Following the AP Ordinance, MFIN retained Glocal, an independent organization with prior experience investigating farmer suicides in India. Glocal’s remit was to establish the facts behind the 87 suicide cases that the AP government alleged to have been abetted by MFIs in the state. According to MFIN President Alok Prasad, Glocal found that the majority of the government’s allegations were unsubstantiated, with many cases showing no link to MFIs whatsoever. As was already evident during the fall of 2010, the AP government was clearly not motivated by a search for truth or a desire to protect the innocent. Its approach was to throw everything against the wall and see what sticks. Moreover, ascribing suicides to unrelated events is a well-established tradition in Andhra Pradesh politics; why should microfinance be any different?

However, not all the charges turned out to be bogus. In its investigation, Glocal found cases that did have strong links between the actions of MFI staff and subsequent borrower suicides. According to Mr. Prasad, “the findings were troubling. MFIN members all took the view that while MFI policies had not been to blame, these actions arose from how they were implemented.” In response, MFIN members have used the report to tighten lending and collections practices, alongside the tightening of MFIN’s own Code of Conduct and the intensified push to implement credit bureau reporting.

Many of these rehabilitation efforts were covered in the press and have helped to some extent improve the industry’s reputation. They are in any case necessary in order to assure that the failures that led to client harassment cannot be repeated again. However, the Glocal report itself was never published. Mr. Prasad emphasized that it had always been meant for internal use only, though the decision to not publish may well have been contentious even within MFIN itself – it was none other than its Chairman Vijay Mahajan who back in June 2011 wrote that the study would be released to the public domain.

The ultimate decision not to publish the study is deeply disappointing. By choosing to hold on to those results, MFIN has also given up its best opportunity to challenge the narrative established in the media during the height of the scandal back in Fall 2010. In many respects, this is similar to its efforts at atonement during that time, when Vijay Mahajan and Alok Prasad were publicly acknowledging the errors of excessive growth and loss of internal control, with the implication that in such circumstances, a loan officer somewhere may well have gone too far. I have no doubt that their statements were heartfelt and genuine, but they nevertheless proved weak tea.

For one thing, apology for a general wrong (“mistakes were made”) is not the same as apology for the thing itself. Recitation of wrongdoing is an integral part of a full apology (think “I’m sorry” vs. “I’m sorry that I hit my sister”). Secondly, neither Vijay Mahajan nor Alok Prasad can realistically apologize for the sins of their peers. That must come from the MFIs whose staff committed these acts, yet none of them have issued any such apologies, let alone accepted responsibility. As things stand, we don’t even know which MFIs we should be asking to apologize – their names have been privy only to those who have seen Glocal’s report. We can only speculate (let’s see… Spandana? SHARE?). At least, thanks to Erika Kinetz, we now know one: SKS. So what’s this only publicly-listed MFI in India been saying about the role of its staff in suicide cases?

Actually, nothing. And also, something. In a particularly strange replay of October 2010 (remember Gurumani’s firing?), SKS is once again enlightening the public with boardroom struggles that could form the script for a soap opera, what with its dramatic characters and sudden plot twists. Individuals morph from whistle-blowers into disaffected employees out for revenge, depending on who you ask. Independent organizations are either commissioned to investigate client suicides or they aren’t, notwithstanding the many email and other trails pointing to their findings. Presentations on suicide cases are either made to the board and individual directors or they aren’t. Between all these accusations and counter-accusations, it’s easy to lose track of the main question: was SKS responsible for any of its client suicides?

The company’s main defense is that 14 out of 15 criminal probes against its staff have been either dropped or resulted in acquittals (one is still pending). On this score, the results support the MFIN/Glocal finding that many of the initial allegations by the AP government were scatter-shot. In the case of SKS, some charges lack that most basic of requirements – that the suicide involve an actual SKS borrower (although some of them involved a husband or another relative). As for its own officially non-existent report that found seven suicides for which staff bear some responsibility, the company’s management claims no knowledge of any of it, according to spokesman J.S. Sai.

More surprisingly still, SKS also appears to have no knowledge of the MFIN/Glocal report. The latter is, frankly, difficult to believe. There is no question that, as a member of MFIN, SKS has full access to this report, which, according to Kinetz, details four cases of borrower suicides where SKS staff “actions appeared strongly linked to the subsequent deaths.” Yet when I requested SKS to share the portion of the MFIN/Glocal report that pertains to the company, the answer I received was that they don’t have it. Either the report does contain these four cases or it doesn’t. Given that SKS was happy to share exculpatory material (such as summaries of the 15 AP criminal probes), but is unwilling to share the MFIN report, I have to conclude that the MFIN report does contain these four cases.

Atoning for the past, building for the future

In my discussions with industry leaders over the past month, I have been repeatedly asked – why am I writing about this now? Is it not better to focus on the future than dwell on the past? Well, yes, it would be better. The problem is that it is not possible to divorce the two. Only by fully acknowledging its past mistakes – in both word and deed – can the sector free itself to pursue a future unimpeded by its tarnished image.

There is at SKS and probably at most Andhra MFIs a sense of victimhood. Such is the extent of their focus on the wrongs committed by the AP government that they fail to see – indeed, they actively try not to see – their own culpability. For there is little doubt that there were instances of severe harassment by the MFIs that may have contributed to borrower suicides. Those cases may be few, far fewer than what had been alleged by the AP government. But they are there nevertheless. It also seems clear that the MFIs, via MFIN and individually, have taken steps to insure that such harassment can’t happen again, and in so doing, they have sought to rebuild their credibility. That is, of course, of critical importance. However, what they have neglected is the first step of credibility management – admitting one’s own wrongdoing and taking responsibility for it.

It’s time to stop circling the wagons. MFIN should publish the Glocal investigation report in full. Each MFI should then apologize and appropriately compensate the families of those victims for whose suicides they were found to have borne some responsibility. Finally, it is high time for the boards of many other large Andhra Pradesh MFIs to display real governance and show their current managers the door, then turn attention to themselves and do some house-cleaning by bringing in new directors (a nudge from RBI would help here). Going forward, the MFIs, under the auspices of MFIN, should submit themselves to annual audits of lending and collections practices, and insure that the findings – however damaging – are made public. And for those MFIs that are more worried about solvency than their public image, it’s worth bearing in mind that if they are to have any future at all, these changes cannot be avoided. Better now than later.

Going through all this at a stage when the sector appears to be recovering may well create difficulty in the short run. It would’ve been far preferable to do this last summer. But despite the passage of time, the underlying absence of trust in microfinance institutions – both in India and abroad – still runs deep. By publicly acknowledging and atoning for their wrongdoing, the struggling MFIs of Andhra can finally start the long process of rehabilitating the sector’s tarnished reputation. Only then can they hope to shake off the heavy burdens of the sector’s sorry past.

Leave a Reply