MicrofinanceFocus, 27 December 2011

On October 14, 2010, the Andhra Pradesh government issued an Ordinance that effectively shut down the microfinance market in the state. That shutdown continues to this day, with collections at negligible levels. It’s clear that the AP microfinance market is dead and will not recover for years.

Important as AP has been to India microfinance, it is not everything. Despite the year-long crisis, repayment rates in other states remain strong. And though AP-oriented MFIs have been seriously or even terminally wounded, others have remained unscathed.

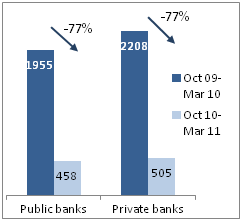

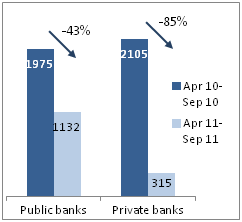

Despite this, in the intervening period funding for MFIs – largely dependent on a handful of Indian state and commercial banks – has persisted in a state of severe liquidity deficit. According to Sa-Dhan’s Bharat Microfinance Report 2011, during the six month period immediately following the crisis, banks curtailed funding by 77% (Figure 1). The subsequent six months saw public banks re-enter the market, though still at nearly half the level of prior year’s funding. Private banks, however, reduced their lending further still, to just 15% of earlier levels (Figure 2). A full year after the crisis, total bank funding is still down by 65%.

Figure 1: Funding flow after during AP crisis (Rs crore) |

Figure 2: Funding flow 6 months after AP crisis (Rs crore) |

This level of funding decline underscores the severity of the contagion that spread from the AP crisis. Before the crisis hit, Andhra Pradesh accounted for just under 30% of the total MFI portfolio outstanding. Yet the drop in bank funding is 2.2 times greater than the AP share would imply.

To some degree, one can attribute this to the fact that several of the national MFIs are based in AP and thus severely impacted as institutions. But this is not the whole story. Bank funding has dried up for many smaller institutions, and has become scarce even for larger MFIs outside of AP. Private banks have almost entirely abandoned the sector. Meanwhile, no one else has been able to step up to try to fill the gap. That is the heart of the problem.

No sustainable business can be built on a single – and fickle – source of funding, yet that is exactly the situation faced by Indian MFIs. In the current crisis, banks have pulled back due to regulatory uncertainty and desire to avoid a damaged sector, but a liquidity crisis can take place under other scenarios as well – a banking crisis unrelated to microfinance, a change to Priority Sector requirements, or other events exogenous to the MFIs could all have resulted in a similar situation.

What the past year has shown is that the sector doesn’t really have serious funding options other than the banks. Foreign funding is not an option, due to regulatory constraints. Deposits are also not an option due to regulatory constraints. The result has been that for the past year, MFIs have been praying for banks to start lending again.

Capital Markets as an Alternative

It is possible that the prayers will be answered, eventually. But unless the sector acts to develop other sources of funding, the underlying vulnerability will remain. Some alternatives have been emerging. Over the past year, MFIs have increasingly turned to the capital markets, using rated securitizations and non-convertible debentures (NCDs) as alternative funding vehicles.

Rated securitizations have become an important channel, with IFMR Capital – the leading arranger of microfinance securitizations in India – issuing Rs 550 crore of securitizations thus far this year. While these vehicles pose significant risks in their own right, the explosive growth of this channel demonstrates the sector’s need for alternative funding sources. Issuance of NCDs has also been very active. During Jul-Aug 2011, Ujjivan raised Rs 55 crore via NCDs, on top of another Rs 40 crore it issued in Jan 2011. Equitas raised 50 crore. Smaller MFIs have also taken advantage of this channel during the year, with Unitus Capital citing a figure of 200 crore raised via NCDs during the first nine months of the year.

These are not new instruments. In the past, they tended to be subscribed by the same banks that are now pulling away from the sector. Given the banks’ concerns, it is reasonable to believe that the investors subscribing to these instruments now represent a broader group. The Jan 2011 NCD issue by Ujjivan was subscribed by an affiliate of Developing World Markets, a US-based microfinance investor. The Equitas NCD was purchased by FMO. Meanwhile, IFMR Capital’s deal announcements during this year have mentioned banks, NBFCs and private wealth investors as subscribers, though it does not generally publish the names.

Developing the capital markets into a credible funding channel is an important part of stabilizing the funding structure of the microfinance sector. It has taken a crisis to force the MFIs to diversify their funding. However, now that this channel has been significantly expanded, it is likely to become a core part of the sector’s future funding structure.

Funding the future

The microfinance sector’s over-dependence on banks is a historical phenomenon. Certainly, the MFIs deserve a fair share of the blame for under-diversifying their sources of funding. But the larger share of blame rests with the RBI, which created and fostered this funding environment through its implementation of the Priority Sector guidelines. By simultaneously disallowing deposit-gathering and foreign funding, while allowing unlimited funding under Priority Sector, RBI created the unstable liquidity situation that nearly collapsed the microfinance sector in the wake of the AP crisis.

Since then, the sector has expanded its use of capital markets into an important and credible funding alternative. This is good news, but it is not enough. With foreign funding still out of reach, the absence of real and convincing access to deposits remains a key stumbling block to developing a more sustainable microfinance industry. The draft Microfinance Bill and its permission to mobilize thrift, shows some promise, though the exclusion of non-thrift deposits is unfortunate. It remains to be seen whether the final version of the bill and the subsequent regulatory guidelines will be appropriate to the market and sufficiently flexible to allow deposits to become a credible funding channel for MFIs.

In the end, only deposits can move the sector to a more stable funding structure and help secure financial access for all Indians. Until the country’s policymakers – both the Parliament and RBI – recognize this, India’s microfinance industry will continue to be hobbled by an unstable funding structure. And the more the sector grows, the more untenable the situation will become.

Leave a Reply