Co-authored with Karuna Krishnaswamy; MicrofinanceFocus, 25 January 2011

Hyderabad has gone missing. And it seems nobody has noticed the absence. While academics and the press were scouring the villages of Andhra Pradesh in search of over-indebted borrowers and debt-induced suicides, and while politicians in the villages and government halls were busy protecting their beloved SHGs (and the vote banks they provide), Hyderabad up and vanished, leaving apparently no trace of its prior existence.

Naturally, we are referring not to the physical city, but to its microfinance market, as well as those of other cities in Andhra Pradesh. Make no mistake – microfinance lending in urban AP has been widespread, outpacing even that of the countryside. And yet, there seems to be little recognition of its existence and how it has been affected by the current crisis. To make matters worse, the Malegam report continues the trend of treating the urban poor like invisible shadows, using group-lending and loan and income caps to effectively proscribe much of the microfinance activity for which they are natural clients.

We don’t believe that it is right to make policy by willfully ignoring the toiling masses of the urban poor, whose ranks hold the next generation of India’s rising middle class. And it is with that in mind that we hope to retrace the path back to the lost cities of Andhra.

Seek the city, for yonder be loans

That there is lending in Andhra’s cities and especially at a large scale may appear surprising given the little attention they generate. But market women talk, as do statisticians’ data, and together they tell an interesting tale. On the latter side, there are two key sources – the annual State of the Sector report, which compiles statewise data provided by the MFIs, and the IFMR-CMF Access to Finance in Andhra Pradesh survey of rural households, conducted in mid-2009. Unfortunately, neither source says anything about Andhra’s cities. So, like with the black holes of outer space, we are left to make observations about that which cannot be measured directly.

By triangulating between the two data sets, we estimate that the number of loans in urban Andhra Pradesh is approximately 2.9 million, or about half of the total loans outstanding (see calculations here[DR1] ). Given that urban households comprise about 30% of all households in the state, this suggests an urban microfinance density that is some 2.5 times higher than in rural areas.

To test the observation, we relied on CMF survey data to evaluate the eight AP districts it covered, separating out three that bordered major urban areas in the state (Mahbubnagar and Nalgonda near Hyderabad,[1] and Prakasam near Guntur), and the remaining five (Nizamabad, Medak, Vizianagaram, Visakhapatnam, and Cuddapah). Our assumption was that the borrowing levels in the villages of urban-bordering districts would be more indicative of what’s happening in the cities themselves.

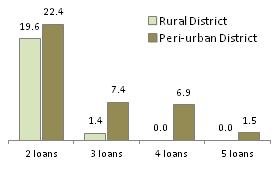

The findings suggested strongly that there is a clear difference in levels of microfinance activity between urban and rural Andhra Pradesh. In the three peri-urban districts, microcredit was more widespread, reaching 12.1% of households, as opposed to 10.7% in the other districts. However, the big difference came from multiple borrowing. In the peri-urban districts, 16% of client households had three or more loans, while in the rural districts, the number was 1.4% (Figure 1). The impact of such lending is very substantial – these 3+ loan households account for a total of 35% of the peri-urban portfolio, whereas in the rural districts, they comprise just 3%. And because these are villages in peri-urban districts, and not the cities themselves, one can reasonably presume that multiple borrowing in the cities themselves must be even greater.

|

Figure 1: Households with multiple loans (% of MFI clients)

source: Access to Finance in Andhra Pradesh survey |

Anecdotal evidence suggests that it is. Conducting an exploratory visit in a few colonies of Hyderabad last month, Microfinance Focus spoke with six MFI clients, of whom 3 had one loan each, 1 had two loans, one had 4 loans, and another implied that she had 3-4 loans, without directly saying so. These were all loans with major MFIs. Naturally, this is far too small a sample to extrapolate from, but given the data peri-urban districts, it certainly supports the contention that multiple borrowing is indeed more widespread in the cities.

The invisible loans

It is stunning that, given these clear indications of extensive microfinance activity and multiple borrowing in the cities of AP, there has been practically no mention of them either during the lead-up to the crisis, or since the AP Ordinance was issued. The media was awash in reporting farmer suicides allegedly caused by MFI strong-arm collections, and government officials were incensed that MFIs were undermining their SHG programs. Yet there are no farmers or SHGs in Hyderabad, and despite far higher levels of borrowing, there have been hardly any media reports linking urban suicides to microfinance. So either the suicides in rural areas are driven by other causes, or politicians and media simply don’t care as much about city dwellers. Perhaps both conclusions are true.

When the Ordinance was issued, it was directed explicitly at protecting the SHGs, stating right in the preamble that “Whereas … SHGs are being exploited by private Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs) through usurious interest rates and coercive means of recovery resulting in their impoverishment & in some cases leading to suicides, it is expedient to make provisions for protecting the interests of the SHGs, by regulating the money leading (sic) transactions by the money lending MFIs.”

The only acknowledgment by the AP Government that cities even exist in the world of microfinance is the requirement that in urban areas, MFIs should register with the local MEPMA Project Director – the urban counterpart of SERP, which is the organization charged with overseeing the SHG program in the state. Then again, the Ordinance also mandates that all repayments must be collected at the office of the Gram Panchayat only. Did its writers intend for the teeming masses of Hyderabad to get on a bus and head to the nearest village, or did they simply forget that there are no Gram Panchayats in Hyderabad?

Given the state government’s fixation on the countryside, perhaps it’s also not surprising that the type of anti-MFI political action commonly reported in villages – preventing loan officers from entering, arresting MFI employees, and so forth – doesn’t seem to be happening in the cities. The Hyderabad clients mentioned above all said that no local politicians have been agitating against MFIs, nor had they even heard of such things.

Waiver contagion

These clients also have not heard of any Ordinance. But they are media consumers, and know that MFIs have apparently been doing some bad things, though what exactly isn’t entirely clear to them. What is clear to them is that a waiver had been announced by the Chief Minister of AP. The fact that this is fiction is of little consequence – rumor is stronger than fact. And so, they have stopped paying, as have all their neighbors. After all, only a fool would pay a loan that’s about to be waived.

This situation doesn’t seem to be limited to the few visited townships in Hyderabad. It is evident from statewide data that non-payment in cities is widespread. Last month, in a downgrade action affecting Spandana, CRISIL stated that the MFI’s collections rates in the state had dropped to 7%. Considering that Spandana reports 56% of its outstanding loans as being in urban areas, the obvious conclusion is that non-payment in Andhra’s cities is at least comparable to that of its villages.

This should not be surprising. Rumors spread faster in cities, and repayment influence – knowledge that others aren’t paying – is stronger due to higher density of borrowers. After all, it is quite conceivable for an MFI to be collecting from one village, while another 10km away might be on a repayment strike. It is far less likely for this to be the case when the next door “village” is across the street. Experience from the crisis in southern Karnataka also supports this assertion, since the surrounding rural regions were less impacted than Kolar itself or other cities. While this is in part due to the weaker influence wielded by the Anjuman Committee on the rural borrowers, it is likely also due to other intrinsic characteristics of rural areas – including strong relationships between the loan officers and their customers.

However, the presence of extensive multiple borrowing, especially at the levels of three loans or more, undermines the MFI position even further. It is intuitive that a household carrying a heavier debt burden would have more to gain from a default. But one need not rely on intuition alone. Once again, experience in Kolar shows this to be exactly the case. A detailed study of 900 customers in the region reveals that the decision to strategically default is significantly correlated to the total debt amount taken, incomes, and number of lenders per colony – all of which are higher in urban areas.

But besides heavy presence of multiple borrowing, an even more insidious factor is the extensive presence of loan agents, who act as intermediaries between the clients and the MFIs. Of the six borrowers interviewed above, two were agents/group leaders. To make matters worse, both of the agents were also heavy multiple borrowers (with 3+ loans), and at least in one woman’s case, these multiple loans all came from the same MFI, with the agent having used fictitious borrowers for the purpose. Such a situation further increases the agent’s incentive to default on her own loans, while influencing her group members to default on theirs.

In a couple of cases, the agents had such a dominant role that the borrowers didn’t even know which MFI their loans had come from. For an MFI seeking to restart collections, this makes the matter that much more difficult. In effect, the MFI will be forced to bargain with the agent if it is to have any hope in collecting not just that agent’s several loans, but also those of the group members.

Looking ahead

With the release of the Malegam report, it appears that the industry may soon enter the beginning of the end of the 2010 Andhra Pradesh crisis. With a new regulatory regime in place, and local politicians presumably instructed to back off and allow MFIs back into the field, one can expect operations to begin to resume at some level. That at least may be the scenario to be played out in the countryside.

The trouble with the cities is that their problem, although sparked by the Ordinance, isn’t at its core a political or regulatory one. While the MFIs have had to abide by the Ordinance restrictions, unlike in the villages, there is nothing that has physically prevented them from venturing out of their urban branches and continuing collections and lending. Yet there is literally no activity taking place. Except for SKS, which had continued some level of contact, the clients in the Hyderabad colonies above hadn’t seen a loan officer for weeks.

So once they head back into the field, how are MFIs to explain to their urban borrowers that the waiver isn’t forthcoming? How does one prove a negative? Presumably, if the Chief Minister were to publicly make such a statement, that might change minds, but how reasonable is it to expect that to happen?

Another complexity will be the large exposure to borrowers holding three or more loans, which is above the limit proposed by the Malegam committee. Assuming this limit is formally adopted, it will create additional obstacles for restarting collections, since such borrowers will know that after repaying, they will be eligible for less than what they currently owe.

Despite all these issues, there is yet a silver lining. All the borrowers interviewed made it clear that they value their MFI loans and don’t want to lose that relationship. They’re not happy with the status quo, where they have no access to new loans. Yet they also want their waiver, and they still have the agents to contend with, whose incentives are quite different from their own. MFIs would be wise to focus on finding solutions to these two issues.

Getting the market back on track will require a great deal of adaptation by the MFIs, both to abide by the new regulations, as well as to rebuild the relationship with their clients. With the apparently impending end of the AP Ordinance and clarity of new regulation, those who care about the sector have reason to hope again. However, until Andhra’s cities are put back on the map, positive outcome – for MFIs, clients, and government – will remain elusive.

[DR1]Add link to excel file

Leave a Reply