MicrofinanceFocus, 7 June 2010

Savings is a hot topic in the microfinance policy circles these days. The CGAP blog regularly features one or another posting on savings programs. The influential blogger David Roodman recently recommended deemphasizing cross-border MFI debt funding in favor of support for savings services. Meanwhile, the Gates Foundation has been channeling its millions towards expanding savings, in many cases bypassing the traditional microfinance sector altogether.

What’s this all about? At a time when credit-only MFIs are raising millions in the stock market, and the Indian microfinance industry is chalking up yet another year of explosive growth, the notion of savings might appear decidedly academic, perhaps even a bit quaint. And yet, this new attention isn’t unwarranted. On the heels of recent research raising serious questions about the efficacy of microcredit as a poverty-reducing tool, and others showing that microcredit is used largely for non-business needs, the idea of savings as the primary instrument for money management seems logical. After all, no person has ever fallen into a savings-trap, been impoverished by too much saving, or been harassed to the point of suicide by an unscrupulous savings collector.

And though it does seem counter-intuitive, to a habitual microcredit client, savings programs are not necessarily very different from credit – she makes the same regular payments week-in and week-out, and gets a lump sum every 50-weeks. True, in one case the lump sum comes at the beginning (the loan), and in the other case, it’s at the end (the withdrawal), but once in the program, the difference becomes obscured after a few cycles or even a few weeks. Stuart Rutherford, who first described the similarity in his ground-breaking 1999 essay The Poor and Their Money has coined a term to describe the savings-like nature of a loan: saving-down, as in taking a loan and repaying it later out of future savings.

Unsurprisingly, as the subject of savings gains prominence, the microfinance policy world is beginning to look beyond the MFIs – to community banks, credit unions, even post offices. That’s right, post offices – institutions that have been around for over a hundred years, largely epitomize the word bureaucracy, and are, frankly, not very exciting. Postal bank managers simply don’t get featured on lists of the most influential, successful, or, for that matter beautiful people in the world. Apparently, expanding financial access doesn’t require any of those traits.

History of Savings Banks[1]

Besides the evident shift in microfinance policy circles, savings also draw substantial support from history. Despite numerous antecedents going back to ancient times, modern microcredit goes back only to the 1980s, and did not become widespread until well into the 21st century. Modern microsavings, on the other hand, has a significantly longer pedigree, originating at the dawn of the industrial era in the late 18th century. Like microcredit, savings services for the then-poor masses of Britain (and later continental Europe and beyond) were not originated by profit-seeking businessmen, but promoted mainly by the socially-minded elite. However, their ethos was quite different from what drives microcredit today – the idea was to help the lower classes become moral, upstanding members of society, with steady saving being largely cast in terms of individual responsibility and self-denial, as Henry Duncan, one of the progenitors of the savings movement argued in 1816:

“It is distressing to think, how much money is thrown away by young women on dress unsuitable to their station, and by young men at the alehouse, and in other extravagances, for no other reason, than that they have no safe place for laying up their surplus earnings.”

For those familiar with the findings of Portfolios of the Poor, the absence of a safe place to save is noteworthy for its similarities with the needs of today’s poor. But the similarities don’t end there. In his 1797 proposal for what he termed “Frugality Banks,” Jeremy Bentham listed a number of situations when the poor might need their savings:

- Failure of employment

- Sickness

- Superannuation [pension]

- Ostentatious burial – a fantastic, yet generally prevalent demand

- Child maintenance provision – in the event of death of the father

- Widow maintenance provision [for support in old age only]

- Marriage fund provision

This list could just as easily apply to any developing country poor family today. Perhaps the one glaring omission is for the education of the children – back in the 18th century the notion of education for the masses had not yet caught on. Finally, perhaps the most striking similarity to today’s notions of microfinance comes from Priscilla Wakefield in 1801, founder of what is considered to be the first savings bank:

“It is well known to those who are conversant with the affairs of the labouring classes, that it is much easier for them to spare a small sum at stated periods, than to lay down what is sufficient…at once.”[2]

This was penned some 200 years before Stuart Rutherford enunciated the idea of usefully large lump sums, and how the difficulty of gathering them drives much of the informal financial markets serving the poor today. Apparently, current research into poor people’s financial needs is as much about rediscovering old truths as it is about finding new ones.

The early promoters of savings banks had clearly hit upon something important. The movement spread rapidly – in some countries, the growth rate was aggressive even by the standards of today’s microfinance sector. For example, France had 27 savings banks in 1833. By 1847, that number had grown to 364, with a savings bank in 93% of towns with a population of 10,000 or more.[3] That’s a level of growth in financial inclusion that any development agency today would be proud of.

Despite their rapid spread, the one persistent issue with savings banks was the risk that hard-earned deposits might not always be safe. Indeed, in the 1840s and 50s, savings banks in the UK had gone through a period of a number of well-publicized frauds, with depositors losing substantial portions of their savings, or in some cases well-heeled bank trustees covering the loss so as to avoid “the censure that would justly have been passed on the laxity of management which had rendered such frauds possible.”[4] The services offered by the banks also left a lot to be desired – of the 638 savings banks active in UK in 1861, over half opened only once a week, and some even less frequently than that.[5]

It was largely in response to these issues that the UK Parliament pushed through a measure in 1861 allowing the British post office to accept deposits. With a single stroke, Britain gained 2481 new savings bank branches that were moreover backed with the full credit of the UK government and the managerial efficiency of one of the most trusted systems of government. The legislators were proven right – by 1906, the UK postal bank, at that time 55 years of age, held 10 million accounts, or some 25% of the UK population.[6]

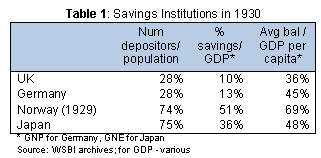

During the course of the 19th century, savings and postal banks spread widely across continental Europe and to industrializing countries far beyond. Though varying by country,  their success in financial inclusion was unquestionable: based on the archives of the World Savings Bank Institute (WSBI), by the eve of the Great Depression, the number of deposit accounts held in savings and postal banks in some countries accounted for as much as 75% of the population (Table 1).

their success in financial inclusion was unquestionable: based on the archives of the World Savings Bank Institute (WSBI), by the eve of the Great Depression, the number of deposit accounts held in savings and postal banks in some countries accounted for as much as 75% of the population (Table 1).

Savings Institutions Today

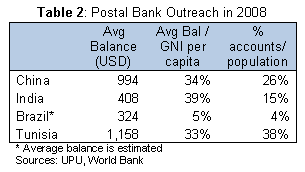

Despite their age, these institutions are far from retirement. In some countries, they continue to play a role as cornerstones for the broader economy: in Germany, the non-bank deposit base of savings banks (Sparkassen and Giroverband) amounts to 42% of the country’s GDP; in Japan, the postal bank’s deposits alone equal 37% of GDP. In many developing countries, the numbers are similarly impressive, with the Tunisia postal bank,  for example, reaching 38% of the population (Table 2). And judging from average balances of these institutions, the clientele being reached is either significantly poorer than their counterparts in the 1930s, or have a generally lower propensity to save.

for example, reaching 38% of the population (Table 2). And judging from average balances of these institutions, the clientele being reached is either significantly poorer than their counterparts in the 1930s, or have a generally lower propensity to save.

For example, according to a study by the Universal Postal Union (UPU), Brazilians living in the poorest half of the country’s municipalities, which represent only 29% of the total population, account for some 50% of Brazil’s Banco Postal deposits. Perhaps no less interestingly, the average deposit account balance to per-capita GNI is only 5% in the poorest municipalities and 6% in the wealthiest.[7] This is by no means an indication of near equality between the municipalities – Brazil is a country of stark wealth contrasts – but it indicates that it is largely the poor, wherever they live, who use Banco Postal services. However, it’s also worth noting that this clientele is very recent – after partnering in 2001 with Bradesco, a major national bank, Banco Postal went on to expand its national presence from 39% of municipalities in 2002 to 85% of municipalities by 2004 – in many cases in areas that previously had no formal financial services of any kind. Thus, it would not be unreasonable to see its average deposits increase as the partnership matures and clients’ savings grow.

Brazil offers only an indirect indication of the likely makeup of its Banco Postal clientele. Fortunately, a WSBI study in 2008 tried to explicitly answer the question: who are the clients of savings banks? Among the four institutions included in the study was India Post.

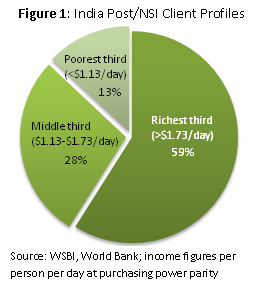

With its 155,000 branches, (90% of them rural) India Post represents the single largest financial outreach institution in the world. By comparison, SKS – the country’s largest MFI – operates 1,627 branches. The WSBI study examined a segment of India Post clients, served via its partnership with the National Savings Institute (NSI), which covers some 55 million out of a total of 175 million India Post accounts. The survey focused on three sample areas deemed generally representative of India – Hyderabad, the nearby peri-urban town of Nizamabad, and surrounding rural areas. While the findings suggest a strong up-market bias, with the richest third of the population comprising 59% of NSI clients (Figure 1), the level of down-market penetration is no less impressive. Indeed, from a financial inclusion perspective  the interesting part of this study is that 41% of NSI clients (and presumably, a similar number of the overall India Post clients) live below $1.73/day – a range that happens to closely mirror the core of the MFI customer base. However, given India Post’s size, this minority of 41% represents 72 million savings accounts, which well exceeds the combined total of all MFI and SHG clients in India. With such an outreach profile and scale, India Post ought to be a major component of the financial access story, yet it remains largely outside the focus of the microfinance community.

the interesting part of this study is that 41% of NSI clients (and presumably, a similar number of the overall India Post clients) live below $1.73/day – a range that happens to closely mirror the core of the MFI customer base. However, given India Post’s size, this minority of 41% represents 72 million savings accounts, which well exceeds the combined total of all MFI and SHG clients in India. With such an outreach profile and scale, India Post ought to be a major component of the financial access story, yet it remains largely outside the focus of the microfinance community.

Influencers and Donors

Despite their general lack of recognition, savings and postal banks are not entirely new in the world of microfinance. As early as 2004, CGAP was already including such institutions in its overview of financial access, while a number of social scientists have been advocating savings services for the developing country poor since much earlier. However, the pace of focus has picked up substantially in just the last year – the combined effects of recent randomized studies that call into question basic assumptions about the poverty-reducing impacts of microcredit and the up-close look at how the poor actually use financial tools provided by Portfolios of the Poor have noticeably altered the terms and tenor of the discussion. Increasingly the conversation is shifting from alleviating poverty to expanding financial access. And once the shift is made, the practical necessity of a socially-driven provider seeking to help the poor loses a significant part of its relevance – if the point is financial access, does it really matter whether the institution providing that access is pro-poor or not? Indeed, an organization exclusively focused on the poor may be limiting financial access to those just above its cutoff line (think Grameen’s ½ acre land ownership ceiling), yet who may still feel themselves unwelcome at commercial banks.

Despite the recent attention, much of the microfinance funding establishment is only now starting to seriously come around to the idea of savings, and especially to the idea of working with organizations other than MFIs. However, at least one donor got the message early on. The Gates Foundation has been the leading funder of savings-related initiatives, with savings and postal banks an important component of its strategy. As Bob Christen, director of the Foundation’s Financial Services for the Poor group, pointed out in an interview,

“Savings banks were set up from day one to be about financial inclusion. That’s where they were founded 100-150 years ago. Over time, the pressure of profitability has caused many to withdraw services from downmarket – no more school-savings accounts, collections in markets. But their mission is still savings. If it was economically viable, they’d be right there. Gate’s purpose is to rekindle that business model. They’re no longer subsidized like they used to be, so we’re bringing new models & new technologies to make it possible.”

Gates may be an early mover, but time will tell whether its strategy will succeed, and whether others will go on to imitate.

Back to the Future

Turning a lumbering ship that has stayed on the same course for decades is no easy task. It’s worth noting that the initial socially-minded orientation of savings and postal banks did not fully transplant to what are today’s developing countries. Many became integrated in corrupt state machinery that saw the government and its employees as their primary beneficiaries rather than the customers these institutions were supposed to serve. Partly in response to such corruption, and partly because of pro-market ideology, institutions such as the World Bank pushed a number of governments to divest of their postal systems’ banking arms, in some countries going as far as forcing their physical separation from the post, thus undercutting the institutions’ core selling point – the postal network and its trusted brand.[8]

In many countries, most of these negative influences have largely been left behind by now. But the two greatest obstacles remain: the staid, slow-moving approach to innovation and market expansion and the continuing absence of customer-oriented focus. The former has its upside, and those banks that have eschewed the new finance of the last decade have done remarkably well during the financial crisis. But when the same static approach transfers over to devising products and strategies to attract harder-to-reach clients, it becomes more difficult to defend – broadening the depositor base might entail many challenges, especially on the operational side, but excessive credit risk is not one of them.

Customer-orientation is a related issue – far too many employees of government-affiliated savings and postal banks tend to forget that they are charged with serving their customers, rather than manifesting the same condescending attitude still so common among government officials. A recent story by UPU’s Union Postale magazine relates a typical anecdote from Bharat Tiwari, a lifelong customer of India Post:

“Like most government departments, there’s a bit of inefficiency. Nothing more or less than you’d find in other government-run organizations.” The other day Tiwari went to open a new account with the post office, but they told him to come back the next day. When he returned, they told him to return the following day. “I would have opened up an account right there and then, but I couldn’t. And I would have saved 500 to 1,000 rupees in that account each month.”

It is difficult to square such an approach to client service with the financial access mission of the organization, and yet by all indications, this is a situation that is widespread not only in many India Post branches, but in a number of other savings institutions throughout the world, notable exceptions notwithstanding.

In fact, both these obstacles – organizational stasis and bureaucratic attitude – stem as much from external expectations as from organizational culture. When an organization is perceived as a government-affiliated dinosaur with little relevance to today’s needs, it is likely to act that way. However, with local governments and international development policy-makers starting to pay more attention to the under-utilized potential of these institutions, change can be accomplished, as demonstrated by the recent success of Brazil’s Banco Postal.

With the new attention they’re now getting, these century-old institutions may yet brush off their dusty mission statements, rediscover their roots, and return to reprise their role as key players in expanding financial inclusion.

[1] A special nod to the ongoing research of David Roodman shared through his open-book blog, which guided me to many of the sources cited here.

[2] David Roodman, Open Book Blog, ch. 3 draft

[3] History of European Savings Banks, Jurgen Mura, editor; Stuttgard, 1996, p. 77

[4] A. Scratchely, A Practical Treatise on Savings Banks, London 1860, p. 58; quoted in ibid, p. 139

[5] ibid, p. 140

[6] David Roodman, Open Book Blog, ch. 3 draft

[7] Jose Anson, UPU, email exchange May 2010

[8] Jose Anson, UPU, phone interview, May 12, 2010

Leave a Reply